Six questions answered about the GBIF Backbone Taxonomy

This past week our informatics team has been updating the Backbone taxonomy on GBIF.org. This is a fairly disruptive process which sometimes involves massive taxonomic changes but DON’T PANIC.

This update is a good thing. It means that some of the taxonomic issues reported have been addressed (see for example this issue concerning the Xylophagidae family) and that new species are now visible on GBIF. Plus, it gives me an excellent opportunity to talk about the GBIF backbone taxonomy and answer some of the questions you might have.

This being a blogpost and all, I cannot write about everything (the building of the backbone in itself is a very long topic). So, if you have any questions relating to this topic, please leave a comment :)

What is the GBIF Backbone taxonomy?

The Backbone taxonomy is actually a GBIF dataset. But not just any dataset, it is probably the most important dataset for GBIF. On its page, it is defined as

a single synthetic management classification with the goal of covering all names GBIF is dealing with.

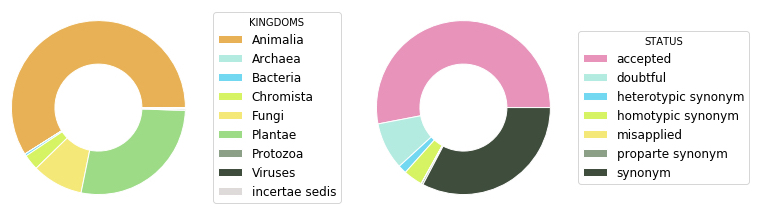

The newest version (September 2019) contains 6,586,578 names. Most of these names are animals. Plus, a large part of these names are actually synonyms (see pie charts below).

If you are interested, I suggest that you browse our web interface or check out the Species API

Why does GBIF need a backbone?

The backbone is needed to organize the data available on GBIF. Without it, we wouldn’t be able to do any taxonomic search and it would be difficult to generate consistent statistics and maps.

As you can imagine, not everyone uses the same classifications or names. This results in considerable variations in higher taxa and a large number of synonyms. The backbone aims to bring all these names together and organize them.

How is the backbone generated?

The backbone is built from other checklists. These include:

- 55 authority checklists,

- a checklist generated from the type specimens shared on GBIF, [EDIT 2024-04-30 the latest versions of the Backbone taxonomy no longer include this checklist as it contained a number of issues and was difficult to update as it relied on many different occurrence publishers.]

- two large sources for stable Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): iBOL Barcode Index Numbers and the UNITE Species Hypothesis identifiers,

- and any checklist shared by PLAZI.org on GBIF (currently 27,054 but not all these were available when the backbone was generated).

These checklists are ordered by priority starting with the Catalogue of Life for most taxa. This order is crucial as it shapes the taxonomy. [Edit 2021-03-09: in the newest version of the backbone from March 2021, the priority list is a bit more complex. Some checklists are used for specific Phyla and will have priority over the Catalogue of Life in the configuration file].

Note that many sequence-based occurrences have no Latin names but are named using species hypotheses (UNITE: fungi) or Barcode Index Numbers (iBOL: primarly animals). This is why adding these two major sources of stable OTUs to the latest backbone taxonomy significantly improves GBIF’s indexing functionality for sequence-based biodiversity data.

Most of the assembly process is automated and the curation happens in the source checklists prior to that. Before reading the rest of my explanation, check out my little illustrated summary (e.g. the animation on the right).

As you can see our algorithm starts with the eight kingdoms, then adds the taxa from the

Catalogue of life before adding other sources in order of priority. New taxa are ignored if their statuses conflict with what was previously added.

Afterward, the synonyms are identified and some infra-specifics are added. Note that:

- The synonyms respect authors.

- The author match is necessarily loose to accommodate variations such as abbreviations.

- Authors are preferred from nomenclators.

- Names that appear only in a nomenclatural database are included but flagged as “doubtful accepted”.

- The same canonical names with different authors are allowed twice, but only one is ever accepted.

Finally, the algorithm identifies the homotypic group of names sharing the same basionym. Only one name is accepted per homotypic group and all the other names are marked as synonyms as they are homotypic. The most trusted first name added stays as the accepted name.

We also add autonyms when needed.

Each node included in the graph representing the new backbone is associated with an identifier (for example, the identifier for Arthropoda is 54: https://www.gbif.org/species/54). Wherever possible, GBIF will reuse the same identifier issued for a taxon concept in the previous backbone.

The backbone building process follows a few more rules, if you are interested I suggest that you check out

these slides on the topic and leave a comment here if you have any question.

The backbone contains major Linnaean ranks of Kingdom to Species plus subspecies, variety and forma. However, it doesn’t include:

- Non-major Linnean ranks (e.g. sub-family, tribe, etc.),

- Hybrid formulas and cultivars,

- Working names (candidatus, placeholder names and non-stable OTUs).

The Catalogue of Life and other institutions work on they taxonomic checklists and review feedback messages all year round.

However, we generate and update the backbone only once or twice a year. As I mentioned before, this is a fairly disruptive process which requires us to put our system on hold while we are re-processing all the data. This means that we re-interpret every single record in light of the new taxonomy (all the names are matched against the new backbone). In the best case scenario this might take 48h. Then we check for any obvious bugs and errors (which can also take a few days). Once everything is in order, the update goes live. During that time, the data content cannot be updated as the ingestion system is paused.

Our informatics team has been laying out groundwork to make this process easier and faster in the future. Thanks to these efforts and the Catalogue of Life + (see the last paragraph), we will have a faster turnover.

Where to report issues?

The backbone isn’t perfect, you might encounter taxonomic errors or spelling mistakes. If this is the case, please report it via our feedback system (see screenshot) or

directly on GitHub. Be as precise as possible and include links and references if available.

We really appreciate all the help we can get and will forward your message to the relevant people.

Missing names and species, what to do about it?

You might find that some names are simply missing from the taxonomy. This happens and we would be grateful if you could report it (along with references).

You can also contribute even more by creating and sharing your own

checklist.

If you are a data provider and that some of the names that you used cannot be found in the backbone, here is what you should do:

- Keep the name as it is but add higher ranks taxa (our algorithm might not recognize the scientific name used but it can still find a higher taxon).

- Add the type status if your specimen is a type (the name will be integrated to the next update [EDIT 2024-04-30 the latest versions of the Backbone taxonomy no longer include type specimens so this advice is out dated]).

- Try some troubleshooting (see paragraph below).

Associated flags: Taxon match none, Taxon match fuzzy, Taxon Match higherrank, what do they mean?

These flags are not related to the backbone itself, they are generated by our matching algorithm when it cannot find an exact match for a given name. The backbone has its own sets of flags associated with the building process. I won’t go into details here but if you are interested, leave a comment.

When you upload a dataset on GBIF, it almost always contains scientific names. Each name is matched to the GBIF backbone taxonomy. Sometimes an exact match is found amongst the names and synonyms of the backbone but not always. Perhaps, the name is missing from the taxonomy or it is mis-spelled? Depending on what can be found (or not), your records might be getting one of the following flags:

| Flag | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Taxon match fuzzy | A match with a different spelling was found. | Pelagodes antiquadrarius and Pelagodes antiquadraria |

| Taxon Match higherrank | No match was found at the same taxonomic rank but one was found for a higher rank. | Hylatomus pileatus and Hylatomus |

| Taxon match none | No match was found. | Flagellate |

As a data provider, there are a few things you can do to avoid these flags:

- You can use our API and/or our name matching tool to check for name matching before you share your data on GBIF.

- Our matching algorithm uses the taxonomic information provided if available (e.g. kingdom, family, etc). Sometimes, just adding the kingdom will help remove any ambiguity in the matching. There are some cases though, where the backbone taxonomy was so different from the one provided that no match could be found, although the species existed in the backbone. If you suspect that this is the case, check the backbone and remove some of the taxa.

- Check technical issues as well. For example, you might get these flags if you provide the author name both in the scientificName field and the scientificNameAuthorship field since these two are concatenated.

The (near) future of the taxonomy: The Catalogue of Life Plus

You might feel like the system I just described lacks some flexibility. Well, you are not the only one. This is why major global initiatives (GBIF, iBOL, BHL, EOL) are currently working on the Catalogue of Life Plus (CoL+ for short). The CoL+ project aims to create a shared taxonomy with a faster turnover, daily integration of newly described species and a more collaborative process. The idea is to have a better, more flexible taxonomy which will be curated by a larger community. We are not quite there yet but if you are interested, please check out their repository.