Search, download, analyze and cite (repeat if necessary)

Finding and accessing data

There is a lot of GBIF-mediated data available. More than 1.3 B occurrence records covering hundreds of thousands of species in all part of the worlds. All free, open and available at the touch of a button. Users can download data through the GBIF.org portal, via the GBIF API, or one of the third-party tools available for programmatic access, e.g. rgbif.

If there is one area in which GBIF has been immensely successful, it’s making the data available to users.

Using data

Data is used a lot, too. One of my responsibilities is to track uses of GBIF-mediated data, especially in scientific literature. This is a somewhat complicated business, explained elsewhere, but as of today (4 October 2019) we’ve logged 3941 peer-reviewed journal articles that to some extent rely of GBIF-mediated data to reach their conclusions.

In other words, people are definitely getting the data AND using it in their research.

Citing data

As is good scientific practice, authors include bibliographic references to other people’s work when citing them in a paper. When you use other people’s data—for instance, obtained through GBIF—the same principle applies. In fact, the Data user agreement that governs use of data from GBIF specifically requires all users to

publicly acknowledge, following the scientific convention of citing sources in conjunction with the use of the data, the Data Publishers whose biodiversity data they have used

and also

comply with the terms and conditions included in the licence selected by each Data Publisher, and the licensing information included with each data download

GBIF provides ready-to-use citations including DOIs for individual datasets (example) and for downloads of records from one or more datasets (example). In the latter example, an author is able to cite the data in a single reference (i.e. GBIF.org (03 October 2019) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.0cgwkh) even though this download includes data from 22 different datasets/publishers.

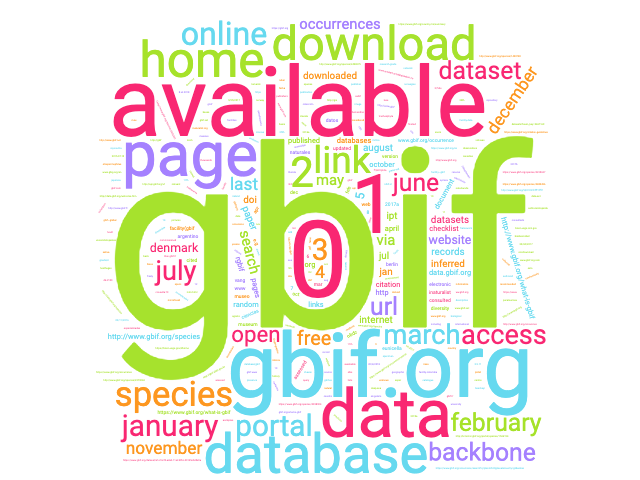

However, getting authors and journal editors to comply with this has not been quite as successful. Of said 3941 papers, less than 10 per cent included a DOI in their citation of GBIF-mediated data. What did the rest do? Cue word cloud:

Countless variations of a reference to GBIF—often the GBIF portal—with one single thing in common: Not one of them acknowledges the data publishers whose work their papers rely on.

The problem

So why are so many authors and/or journal editors getting this wrong? I’ve been reaching out to quite a few of these and these are some of the responses I get:

“we forgot to include the DOI…”

“simply a mistake that was not caught in the proofreading stage…”

“very difficult … putting them all in the references of one paper with limited length would also be impossible”

“I don’t remember seeing the information about specific DOI when downloading”

etc.

So there’s a definitely a human problem here. But to some extent also a technical one that hasn’t really been sufficiently addressed.

Searching for data vs. downloading data

When you go to GBIF.org to get data, the search interface that allows you to select and filter data by taxa, time, geography, etc. is powered by the GBIF search API. This is of course invisible to users of the portal. They will simply do their search and refine filters until they have the data they want—and then download it—ready to use and cite.

A lot of users, however, access data using the search API—either directly or through a third-party tool, like rgbif or pygbif. Because the search API is fast and able to provide most users with all that they need, most simply retrieve that data directly without going through the download step. This means they won’t have a DOI to cite and there’s no persistent record of the data downloaded.

This is a problem because 1) the majority of these API users do not acknowledge the data publishers at all, and 2) their research is often ends up being unreproducible. While the latter is a problem for science, the former is a violation of the GBIF user agreement.

The solution?

For users getting data through GBIF.org we need to be better at emphasizing the importance of citing using DOIs. We will continue to work with authors and journal editors to improve this.

For API users—with the exception of a very narrow set of use cases— I believe everyone should be able to incorporate a “download” step in their data processing. I’m not advocating against using the API at all, but merely arguing that it makes sense to use the search API for preliminary searches and filter refinement—and then using the download API for finally obtaining the actually data to be analyzed. Or if it’s easier to use the data straight from the search API, just do a download with identical filters, log the DOI, and you’re set. You don’t even have to wait for the download to finish!

In practice, this is already very easy to do in e.g. rgbif, as two routes are offered for obtaining occurrence data: occ_search and occ_download. Other tools, however, do not provide this feature, so users need to take extra, sometimes complicated steps to comply with the user agreement. For instance, dismo doesn’t not provide any way of triggering a download and/or citing data.

Bottomline: If an API user is unable or unwilling to go through these steps required to acknowledge data publishers, they should not be using the API for getting data. We need to ensure that our guidelines reflect this and that third-party tools highlight that users are responsible for providing due credit to data publishers.